This part of the world has lots of steep-sided, flat-topped hills known as “mesas,” the Spanish word for table. Mesa Verde is Spanish for “green table,” while my last campsite was known as Blue Mesa. So I went from the blue table to the green table to see Mesa Verde National Park. Of note, as far as I can tell, Blue Mesa is not the name of an actual mesa rock formation, but is applied to the area around Blue Mesa reservoir and Blue Mesa mountain pass. Mesa Verde… well, I’ll explain more about that in a minute.

First, though, a word about RV Travel Logistics. In my last post, I mentioned that when I visit multiple parks in the same general area, I have needed to make the calculation about whether to visit each park as a day trip from a central base of operations or to take my RV close to that park. I was able to visit Black Canyon and Great Sand Dunes from my base at Thousand Trails Blue Mesa (where I can camp for free with my membership), so that made sense. My original Plan A called for me to do the same with Mesa Verde. But even under normal conditions, that was going to be a 3.5 hour trip each way, which is really pushing what was feasible for a day trip. With the wonky bridge on US-50 adding at least an hour to the drive, that plan went out the window.

Plan B was to leave Blue Mesa a day early (Friday), get a campground for two nights at Ancient Cedars Mesa Verde (a commercial campground right at the park entrance), visit Mesa Verde on Saturday, and move onto Utah on Sunday (pushing my Utah park reservation back one day). I made the arrangements for that, but then ran into two problems. First, one of the main attractions at Mesa Verde are the ranger-led Cliff Dwelling Tours. Mesa Verde’s whole reason for existence are the spectacular cliff dwellings left by the Pueblo people. I wanted to do the Cliff Palace Tour (the largest cliff dwelling in North America), but I forgot to jump on the tickets as soon as they opened two weeks in advance, and by the time I remembered to look, Saturday was sold out. I bought the last ticket available for Sunday. I could have gotten Saturday tickets for the Balcony House Tour, but the tour description on the website includes this: “On this one-hour tour to Balcony House, you will climb a 32 ft (9.8 m) ladder, crawl through an 18 in (45 cm) wide by 27 in (68 cm) tall tunnel extending 12 ft (3.7 m) long, and climb up a 65 ft (20 m) open cliff face with 31 ft of steep uneven stone steps and two 18 ft (5.5 m) ladders to exit.”

No thank you very much.

So I was locked into visiting Mesa Verde on Sunday anyway, and then I also found myself needing Friday to take care of some RV reorganization and errands after a very busy work week. So I switched to Plan C: I didn’t leave Blue Mesa until Saturday (as I had originally intended in Plan A), and spent Saturday night at Ancient Cedars Mesa Verde. I was actually double-booked for Sunday night at Ancient Cedars and my Utah campground; while I stayed the night in Utah, it was worth the extra money to not have to worry about checkout time at Mesa Verde so that I could leave my RV in its place and plugged into shore power while I explored the park.

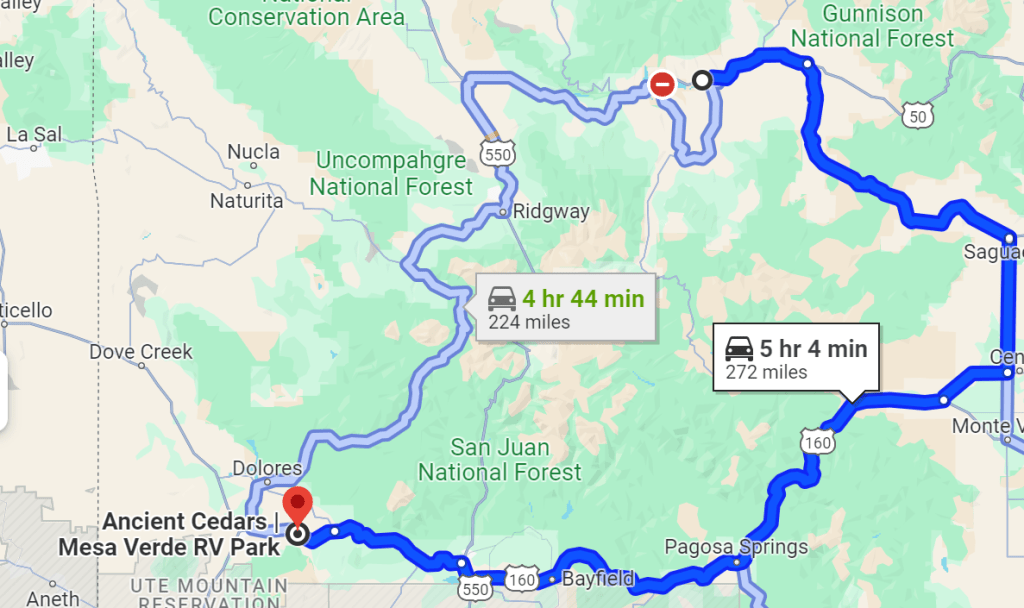

The next question was which route I would take from Blue Mesa to Mesa Verde. The “normal” route, and the shortest one, would have been west along US-50 to US-550 south through Montrose (passing Black Canyon). With the bridge itself closed to RVs, this route would have involved a detour over 20 miles of dirt road to get around it, adding an hour to the trip and requiring me to align my schedule with the times the single-track route was open westbound. An alternate route went the long way around eastbound on Colorado 114, taking me back near Great Sand Dunes. I came back that way last week and knew that the road was beautiful, but steep and very curvy in places, with no passing lanes (which is a major consideration for an RV… there are times when my top speed is 30 mph or less on steep grades and I HATE the pressure of having people stuck behind me). A third route on Colorado 149 looked like the shortest on paper, but had the longest drive time (probably because of its low speed limits through the passes).

(The CO-149 route isn’t marked on here but it’s that gray road right down the middle.)

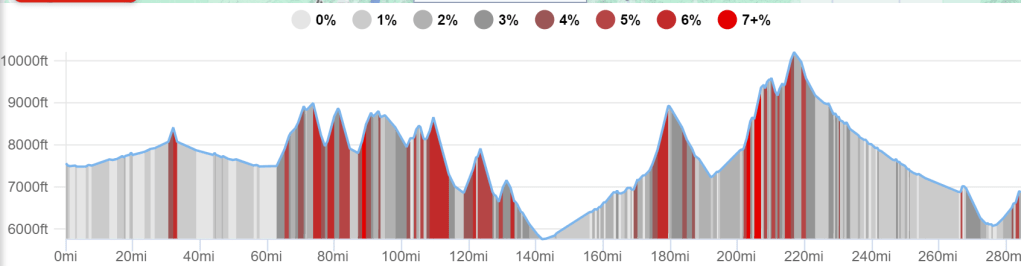

In the end, my decision came down to elevation and grade profiles. I discovered that the RV Life Pro subscription app I got a while back has a VERY nice tool for this. (They also have RV-specific GPS to help avoid things like low underpasses, but I think I prefer regular Google Maps GPS for on-the-fly use. But RV Life’s planning tools are excellent as a reality check on Google Maps in advance.) So, the elevation profiles for the routes:

Those 7+% grades (both up and down) are kind of brutal in a large vehicle, but clearly I wasn’t going to be able to avoid them entirely. All in all, the CO-114 route looked the least painful, so that was my choice.

It turned out to be a good choice. I don’t know what it is about that road, but it just makes my heart sing with its beauty, both when I drove it northbound in my truck last week and going southbound in my RV this time. The lack of passing lanes ended up not being an issue because traffic was so light; I only had other vehicles behind me twice in 60 miles, and they were quickly able to pass me both times, to our mutual satisfaction. I put on my mountain scenery music playlist, and it was perfect.

I don’t know if I can explain this, but… there is one little clip of instrumental music, just two bars from a movie soundtrack, that has a special spiritual significance to me. (Maybe I’ll tell that story someday.) In timing that I could not possibly have planned, that flourish of trumpets was playing at the exact moment I topped the crest of North Pass (the first big peak in the profile) and came into view of the heart-stopping line of blue mountains beyond it. I found myself whispering a prayer of thanks for God’s gift of Beauty. When it comes right down to it, that’s what I am chasing in all my national park travels. I’ve seen a lot in the world to disillusion me in the last few years and I could easily get hard and cynical, but beauty helps keep my faith alive. So I drove down that steep grade with tears rolling down my cheeks, which maybe isn’t the best for driving safety, but was healing to my heart.

I made it safely to my campground Saturday afternoon, and got up early Sunday morning for my Mesa Verde tour… so early, in fact, that I had to wait 15 minutes for the Visitor’s Center to open. I wanted to see the Visitor’s Center displays first because I honestly knew very little about Mesa Verde and needed some context for what I was looking at.

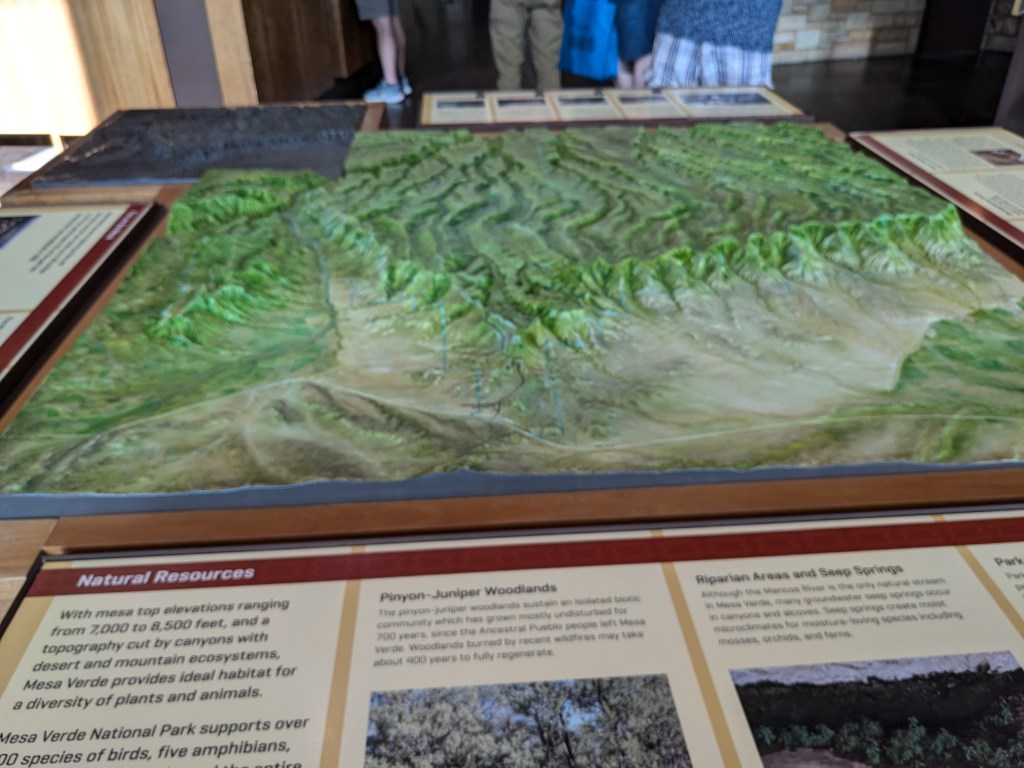

The area known as “Mesa Verde” isn’t a singular rock formation. Nor is it technically a mesa in the geological sense because it is tilted at a 7% angle to the south rather than being flat — what geologists call a cuesta. But that tilt is what made it good for agriculture and thus shaped its history. The top of it is not at all a smooth plain like a tabletop, either. It is scored with ridges and valleys and canyons, breaking it up into several smaller mesas/ cuestas with vertical cliffs in between (creating the space for the cliff dwellings). But the whole system forms a distinct highland elevated far above the surrounding valley floor. As I wound my way up its northern wall on the park entrance road, I found myself thinking of English moors. Though I’m sure their geology and flora and fauna must be very different, Mesa Verde has that same feeling of a piece of land lifted up into the sky.

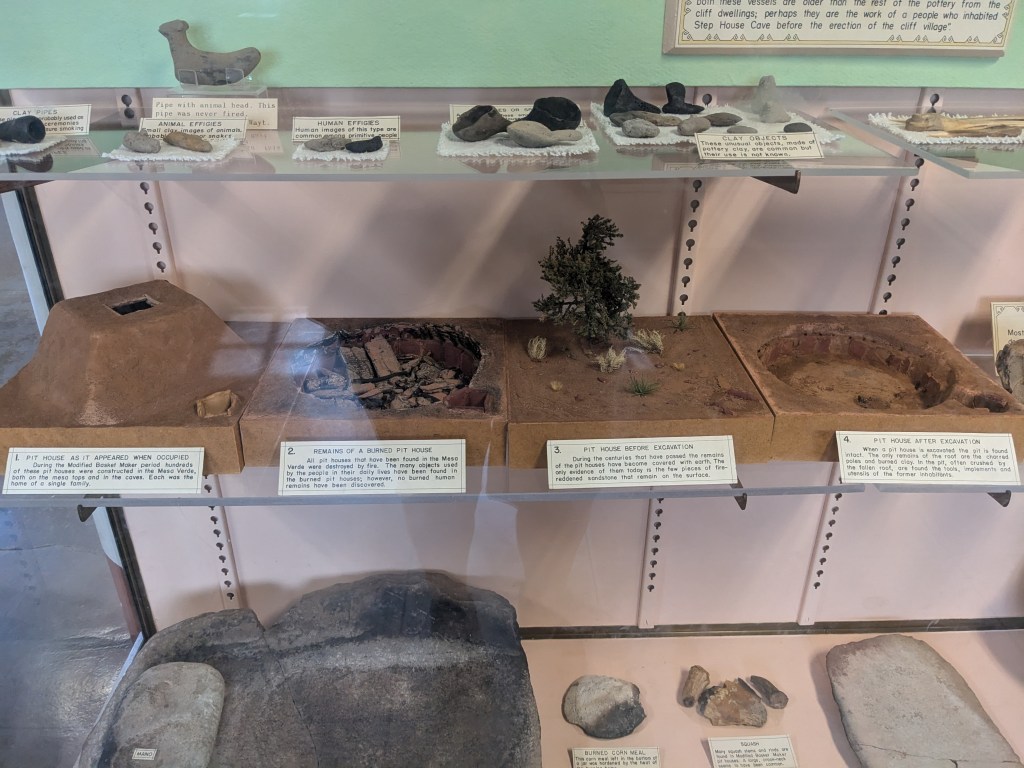

The people now known as the Ancestral Puebloans made their home on Mesa Verde for about 750 years, from 550 to 1300. They farmed on the tops of the mesa, which had a more temperate climate than the valley floor and rich topsoil borne in by the wind. For much of that time, their homes were also on the top surface of the land. They built pit homes – shallow pits with a built-up walls and roof that provided some insulation from heat and cold. In time, this evolved to kivas – deeper holes with a solid roof. Some of these shelters were on the surface, and some in cliff alcoves just below the surface. And then, starting around the year 1200, they began constructing elaborate villages in the larger cliff alcoves that included both kivas and built-up brick rooms, with family living spaces and storage for their “three sisters” crops of corn, beans, and squash.

Sometime around 1300 they rather abruptly and mysteriously left, abandoning the homes they had carved and built out of the cliffs with enormous labor. When non-native settlers first “discovered” the cliff dwellings in the late 1800s, the narrative that emerged was that the Puebloans had “disappeared.” But that’s not really true. There are at least 75,000 modern Puebloans alive today, some still living in pueblos like Acoma Pueblo in New Mexico that bear a remarkable architectural resemblance to the ancient cliff dwellings. They also still make amazing pottery and artwork with the techniques passed down from their ancestors. (I saw some for sale in the gift shop.)

The Puebloans’ own oral history records the migration from Mesa Verde to new homes in Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, but simply says “it was time to move on.” Modern archeology offers some potential reasons, with evidence of drought, famine, and social conflict on the mesa. Whatever the reason, they did move on.

The thing that’s striking to me is that the cliff dwelling villages were only in use for about 100 years… and considering the many years it took to build them, some parts of them were abandoned almost as soon as they were finished. The Puebloans took those architectural skills that they learned and applied them elsewhere in their new homes, but it almost seems like a waste that those amazingly well-built constructions that have withstood over 700 years of time got such a short period of actual use. But then I think about our modern construction practices, and the way we spend millions of dollars to put up a new building only to tear it down or completely remodel it a few years later to suit our changing tastes and needs. A hundred years is a blink of an eye in the geological scale, but it’s several generations in the human scale. How many things that we built in the 1920s have since been torn down, before they got old enough to have “antique” glamor?

Once, I’d gotten myself oriented at the Visitors’ Center, I set off on my drive into the park, climbing the wall in switchbacks up onto the mesa top.

The top of the mesa is very diverse, with green grassy and shrubby areas interspersed with juniper and pine forest. Sadly, over 70% of the park has been burned by wildfire since it was founded in 1906, much of it in the last 30 years, and there are huge patches of fire scar with the dead skeletons of trees sticking up amongst the grasses. Fire is a natural and important part of the mesa ecosystem, but the more recent fires have been hotter and more devastating than normal. From what I could see, the trees haven’t made much of a comeback even in areas that burned 30 years ago; it looks like the mesa environment has been permanently altered. Park rangers are doing their best to preserve what’s left with stringent fire-spotting activity and controlled burns to reduce fuel for wildfires.

The goal of my drive was the Cliff Palace for my 11:30 a.m. tour, but I stopped off along the way to see the sights. Because the mesa is so huge, they warn tour participants to allow 75 minutes to drive from the entrance to the tour meeting point! I was listening to the Guide Along audio tour for Mesa Verde, which offered a lot of good pointers as well as some of the information about the Puebloans that I shared above. One point of interest was the museum at Spruce Tree House Point. Not only does it have some interesting exhibits and a film that lets modern Puebloans tell the story of their people, but the building itself is interesting. It was constructed in 1922 in a style known as “Revival Puebloan” out of the same sandstone rock that the cliff dwellings are made of, with white plaster walls inside. I thought it was very attractive and appropriate.

I reached Cliff Palace in good time for my tour, and had time to look down on it from above as the previous tour group was finishing up.

Our ranger guide marshalled us all together and gave us some safety instructions, then marched us down to the cliff dwelling level. This involved modern metal stairs, rough stone stairs, a short trail, and a climb back up a ladder.

The Cliff Palace is a truly impressive construction, especially when you consider that the builders had to bring in all their supplies down the cliff face without the benefit of the trail that we followed. They dug down and built up into the alcove until they had kivas, rooms, and towers for perhaps 100-150 people.

There are dozens of smaller cliff dwellings in the area, as well as the remnants of pit homes on top of the mesa, and it is theorized that much of Cliff Palace was actually designed as a meeting place, a home for religious and cultural ceremonies, or even a school for the children, in addition to the people who lived there.

Now it is a haven for birds. We saw these eagles circling overhead, and there are swallows living in the cracks of the cliff just above the dwellings.

The Puebloans incorporated this fallen boulder into their architecture. One of the other guests asked the ranger if the big crack in it was cause for concern for the preservationists. The ranger said that, amusingly, there is evidence that the crack was present 750 years ago and it worried the Puebloans too… they apparently made some attempts to stabilize it! If it hasn’t fallen apart in all this time, I don’t think the modern preservationists have too much to worry about.

This square-windowed chamber high above all the rest, right under the alcove roof, was apparently a food storage chamber. Weirdly, it reminded me of a movie projectionist booth under the ceiling of a movie theater.

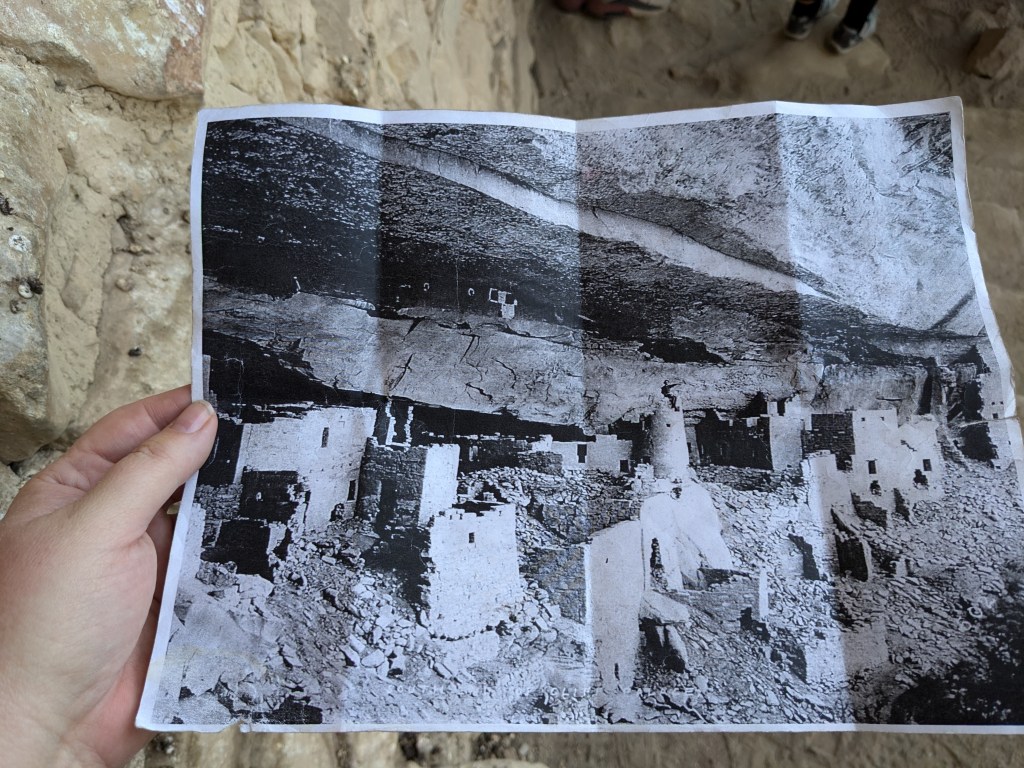

The ranger showed us pictures of what Cliff Palace looked like in the late 1800s when non-native settlers first encountered it. It’s been cleaned up a bit since then and made safer for tourists, but it’s really not that different!

The kiva design was pretty efficient and suited to the Puebloans’ needs. They made deep pits in the ground (either under a cliff overhang as part of cliff dwellings, or on top of the mesa). The walls were thick stone, insulating them from heat and cold. They laid beams along the edges on top of the stone pillars, weaving them together to form a roof.

Apparently the resulting roof was more or less level with the ground and strong enough not only to walk on, but to dance on. Thus, the people could live in the space below and use the tops as a public plaza. The fireplace in the middle vented its smoke through the entry hatch in the top (reached by a ladder). There was a second ventilation shaft in the wall to let in fresh air, but the short stone wall behind the fireplace shielded the fire from drafts and reflected heat back into the rest of the kiva to keep the family warm in winter. It was a clever design showing a good understanding of the physics of hot and cold air. (I think our modern builders could stand to take a lesson or two from that!)

It so happens that there was a family from Galveston who was part of the tour as well; they had just driven up from Texas in the last few days. I ought to have been a little more acclimated to the altitude than they were, but I can’t say that I am. I won’t lie, the climb back up the cliff was hard work and left me breathing pretty hard. There were a bunch more very steep steps and three ladders involved. But we all made it up in the end!

With the tour finished, I did some more driving around with the Guide Along audio tour, but it was too hot (over 90F) for any lengthy hikes. I did get some nice views of the canyon, including a view of Cliff Palace from the opposite side.

There was also the foundation of a pit house from AD 600, the opposite end of the time scale for the Puebloans’ tenure… much shallower than the later kivas, but with some of the same fire pit design.

And there was the mysterious Sun Temple, which seems to have been used for religious/ ceremonial purposes and to have some kind of alignment with astronomical events, though its exact purpose is not reflected in any written or oral history.

There are dozens more spots that I could have visited in the park, including a lot of other cliff dwellings, but I felt like I had gotten a good representative sample. So I headed back over to my campground, got my RV packed back up, and set off for Utah. Stay tuned for my next episode!

Leave a comment