Oops. I’ve neglected this blog shamefully this summer. There’s a lot I could say (and will say, in a future post, hopefully) about the great time I’ve had in Tennessee and Virginia so far this year. But today I wanted to make more of an “education about RV life” type post regarding a very relevant current topic: preparing for extreme weather, and specifically hurricanes.

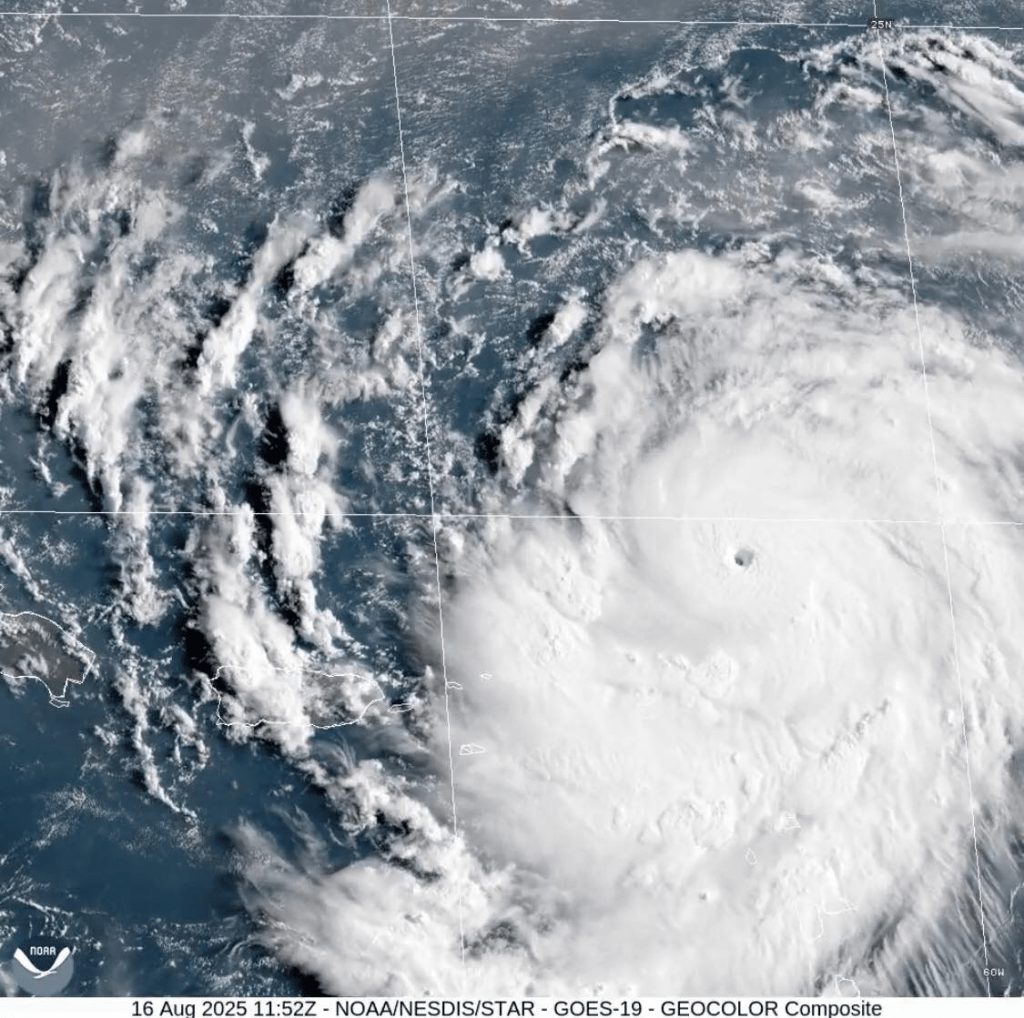

If you haven’t been watching the news, Hurricane Erin has spun up “explosively” to a Category 4 in the Atlantic right now:

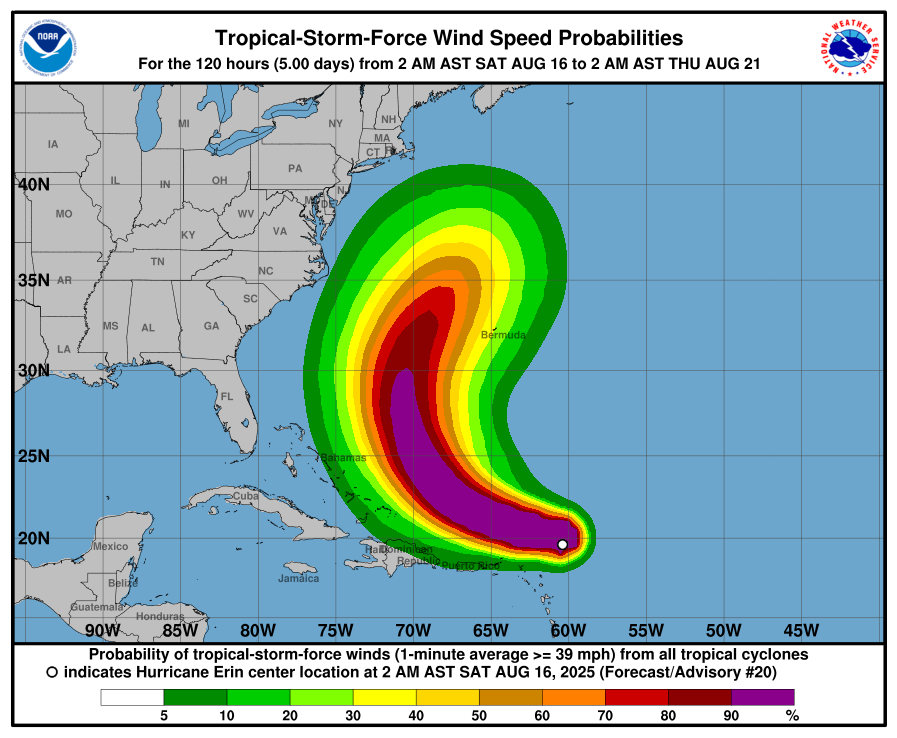

This makes me sit up and pay attention because I’m camped within a couple hundred yards of the Atlantic on the coast of the Delmarva Peninsula (in Virginia). Thankfully, the storm is expected to curve back out to sea and to miss the coast entirely.

But that’s pretty close for comfort, and obviously I am watching this one VERY carefully. If there are tropical-storm-force winds on the eastern edge of that green band, that will have implications for me where I’m camped on that skinny southern peninsula tip.

I am supposed to be camped here until next Saturday morning, but if I have any doubts about the weather, I will pack up and go inland. So I thought this might be a useful time to talk about the calculations that go into that decision for an RVer, which are slightly different from the calculations you might make in a beachhouse or an inland home.

The benefit of an RV in any kind of severe weather is that you’re not limited to one location; if you have enough warning, you can drive away and take all your possessions with you. The downside, of course, is that RVs are terribly unsuited to stand up to severe weather. Wind can easily flip them. Water can sweep them away. So unlike a house, where you must ask yourself, “Am I safer if I stay or if I leave?” the answer in an RV is nearly always, “LEAVE!”

How much warning you need depends somewhat on how you’ve set up your site, how many accessories (chairs, tables, bikes, etc.) you’ve pulled out, whether you are fully hooked up, and whether you have a tow vehicle or a towed vehicle to attach. (I have a towed vehicle, or “toad,” since I drive a motorhome with its own engine and pull my truck behind.) If I’ve been at a site for a while and gotten settled in, I might normally spend an hour or two packing everything up and securing it. But in an emergency, I think I could get that down to 20-30 minutes (if I take the time to hitch up my truck) or 5-10 minutes (if I abandon the truck and my accessories, and just unplug the RV from everything and drive it away). With less time than that, I’d jump in my truck and run for my life, just like anyone with a fixed house would have to do. It also makes a difference whether we’re talking about driving a hundred yards uphill to escape rising water, or driving a hundred miles to escape a fast-moving wildfire, to determine if I could get away with things like leaving my slides out or not taking the time to properly stow my power cord, or moving the motorhome and the truck separately instead of taking time to hitch them together. (I sincerely hope I never have to find all this out the hard way, though.)

The tragic consequences of RVers having NO warning were all too apparent in the Central Texas floods this summer:

People love to camp in beautiful places near rivers, oceans, and wilderness areas, but that makes campgrounds uniquely vulnerable to floods and wildfires. With the realities of campground location and RV construction, RVers need to maintain above-average situational awareness of local weather and to take responsibility for their own safety rather than blindly relying on weather warnings that are more geared toward permanent residents in fixed buildings.

With that said, here are three factors RVers should take under consideration (and how they apply to my current situation):

- Location

- Water

- Wind

Location: As with any real estate, location is everything when it comes to deciding where to park your home on wheels. You must consider both the vulnerabilities of the place where you are parked (with the type of weather hazards or other hazards that are likely to occur), and any potential difficulties of driving away if evacuation becomes necessary.

This works on both the macro and micro level. For example, when I visited Florida two years ago, I chose to do so in May, before the start of hurricane season. Not only is Florida right in the midst of hurricane alley, but its unique shape means that it can be HARD to get away from a storm’s path without driving hundreds of miles. I just didn’t want to deal with the risks of hurricane season there.

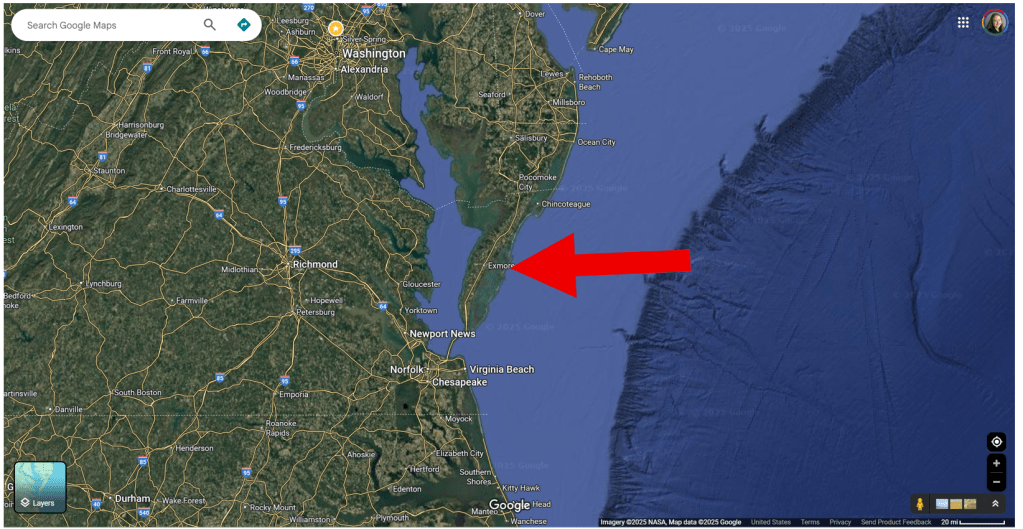

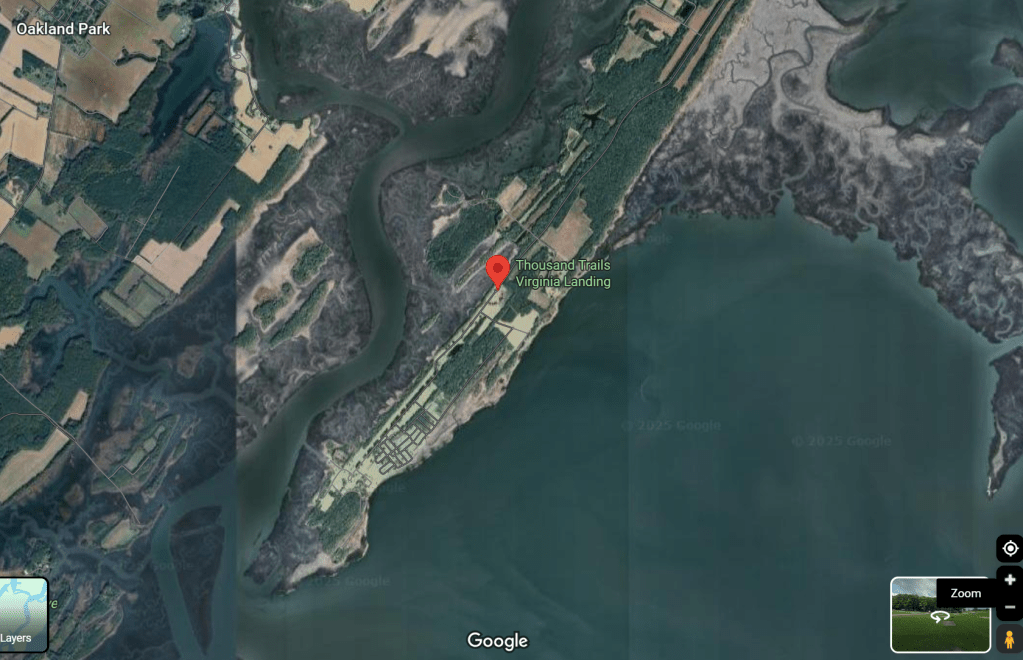

In my current location, I’ve assessed the micro-local and area-wide risks. For starters, I’m on utterly flat ground that’s pretty much at sea level, with no easily accessible higher ground nearby. I’m on a little peninsula that sticks off the side of the larger Delmarva Peninsula like a tiny fractal copy of it. The Atlantic is to my east and south; the estuary of a river is to my west.

I have to drive northeast about 7 miles before there’s a bridge over the river back to the main part of the Delmarva Peninsula. The configuration reminds me of the Bolivar Peninsula at home; it sticks out across the mouth of Galveston Bay, with the bay to the north of it and the Gulf to the south, and one 30-mile road connecting the whole length of it to the mainland. I vividly remember Hurricane Ike, which drove storm surge into Galveston Bay and completely engulfed Bolivar from both sides, destroying nearly every man-made thing on its surface. People got trapped because the road was under water and they had nowhere to go.

On a larger scale, the whole of the Delmarva Peninsula is kind of like that, too. It has the Atlantic on one side and Chesapeake Bay on the other, and to get away from the water you either have to drive a long way north up through Maryland, or go south the way I arrived here over the Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel connecting to mainland Virginia.

The bridge/tunnel is fascinating as a piece of infrastructure architecture, but NOT a place I’d want to be driving an RV in a storm. It alternates between high bridges arching over the water and tunnels running beneath it, to allow shipping to enter Chesapeake Bay. But I can’t even imagine the wind drag on high-profile vehicles in a storm, or what a nightmare traffic would be in a general evacuation. If I do decide I need to evacuate from here, I’ll either do it early enough that those aren’t factors, or I’ll go north.

Water: RVs have the same vulnerability as cars to flood water. It doesn’t take much to sweep one away. It’s a paradox: where a brick-and-mortar home might be damaged by a few inches of flood but still be structurally sound and its inhabitants safe, a few inches of fast-moving floodwater can be a life-threatening emergency to inhabitants of an RV (even if the water isn’t yet high enough to enter the living area). And once your tires are in standing water, it is already very dangerous to try to drive away unless you can see safe ground immediately in front of you.

As I already said, I am doubly surrounded by water here — the Atlantic and the river and Chesapeake Bay. My biggest concern with Erin is that even if it doesn’t hit land here and curves back out to sea as predicted, they are talking about dangerous tides and rip currents along the East Coast. We’re a little bit sheltered here from waves by a chain of barrier islands that I can see out my window, so the water in front of me is more like a bay than open ocean. But I imagine that even a little bit of storm surge could bring it up over the marshes and into our campsites. This is where hyper-local knowledge becomes important — knowledge I don’t have just by looking around me here. I don’t know exactly how much surge it takes to flood this place, or to endanger the road to the north. Depending on what Erin does in the next couple of days and what the forecast track looks like, I may be asking the campground manager these questions so that I can make an informed decision about whether and when to leave. Even if the storm “misses” and there’s no general evacuation, I don’t want to be here with an angry sea lapping at my doorstep.

Wind: Wind is more of a factor in an RV than it is in either a house or a car. RVs are high-profile vehicles with a huge, flat, exposed surface area and a high center of gravity. They will rock ominously even in a wind of 20-30 mph, less than tropical storm force, and in higher winds they can blow over completely. I think wind is the factor least likely to actually endanger me right now with Erin, but if it generates a huge windfield and rocks my RV like a cradle, I would consider moving to get away from that. I like for my bed to hold still while I sleep, thank you very much.

SO, all that being said, the storm is still days out and I don’t have to make any decisions right now.

I’m going to take my bike and kayak up to Assateague Island and go say hello to the wild ponies, which is why I came here in the first place. 🙂 But if I do end up moving my RV early, I’ll post updates on my Facebook and I’ll try to explain the reasons for my decision. Hopefully I get to stay here another week as planned!

Leave a comment